game theory of relationships

incentives, payoffs, and strategy

Game theory is the use of mathematical models to describe strategic interactions. It’s typically associated with economics but also used in other academic areas i.e. math, politics, and computer science. Game theory can be used to explain interactions between people, businesses, governments, maybe even one day, AI machines.

However, what happens when we apply the logic, strategy, and incentives of game theory to relationships where the currency is effort and vulnerability and the payoff is connection. We often think of relationships as more emotional or human. However, humans interactions also often follow certain frameworks.

Eric Berne famously wrote a book called “Games People Play” where he talks about games as a “series of transactions that have a predictable pattern.” In his view, however, games often lead “unproductive outcomes.” For example, he talks about the “see what you made me do” or the “why does this always happen to me” games.1

Game theory, however, focuses more on strategic frameworks. It’s not meant to model specific interactions or make a judgement on conscious or subconscious motivations. Instead, it allows you to assign values to payoffs and indicate if outcomes are optimal or suboptimal. Motivations are still relevant since they impact incentives.

In this way, I think game theory provides a more broad and helpful frame of reference or “mental model” to think about relationships. In this essay, I want to go through some of the most common game theory frameworks and how they could apply and inform certain relationship dynamics. I’ll start with the prisoner’s dilemma.

Prisoner’s dilemma: when optimal strategy leads to suboptimal outcomes

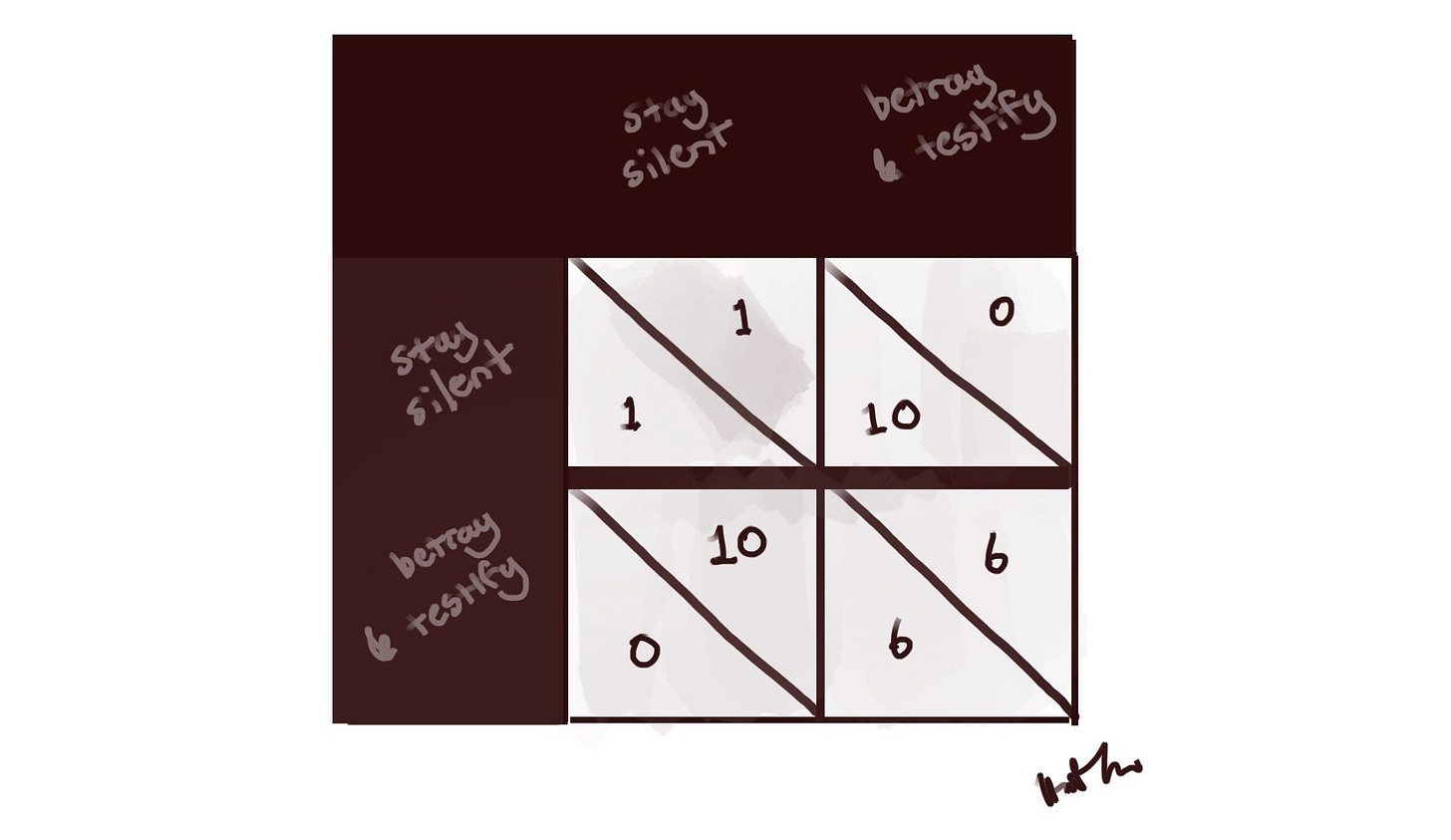

The most well known “game” in game theory is the prisoner’s dilemma. Let’s walk through an example (feel free to skip this section if you’re well-versed in the game):

In this game, there are two prisoners (Prisoner 1 and Prisoner 2). Both prisoners have the option to separately lie or confess to a crime with an associated payoff for each.

Prisoner 1 has the option to lie or confess.

If Prisoner 1 confesses, the outcome can be a 1 year sentence or a 10 year sentence.

If Prisoner 1 lies, the outcome can be going free or a 6 year sentence.

Prisoner 1 should always chose to lie because in both cases, the result is better. And vice versa, since Prisoner 2 has the same optionality in reverse.

In the end, both Prisoner 1 and Prisoner 2 end up at the “nash equilibrium” which is a suboptimal outcome for the game but a result of each Prisoner playing their optimal hand.

If we we replace “prisoners” with “friends” and instead of lies and testify, we base it on “effort” put into a new friendship, then we see a similar outcome.

The optimal strategy for both sides is often to not put effort in to avoid not being hurt if the other side does not reciprocate. This is even more deeply acute when we think about romantic relationships where the effort is higher, the risk of loss is intense, and potential for gain is meaningful.

Unfortunately, this game does lead to a suboptimal outcome i.e. the “nash equilibrium.”

However, what if we begin to incorporate more complexity to the game. In economics, we also have “symmetric” and “asymmetric” games. The prisoner’s dilemma is a symmetric game because both players have the same outputs in each scenario. What if this wasn’t the case?

Asymmetric games: when one person has more power than the other

One example of an asymmetric game is the ultimatum game. In this game, one player has to give the second player an ultimatum. If the second player accepts the ultimatum, the money is split accordingly. Alternately, if the second player rejects the ultimatum, both players get nothing. The split can be either “fair” or “unfair.”

The studies of this game show that there are a lot of differences on both sides based on things like societal expectations of fairness and framing of the proposal (giving vs. splitting vs. taking). It’s interesting to think of how this applies in relationships where we use emotional currency.

One area is marriage proposals. In a marriage proposal, one individual (typically the man in a heterosexual relationship), offers for the woman’s hand in marriage. The woman can either accept or reject the offer. This begs the question, how do women determine what is fair vs. unfair?

Is there something inherent to being “offered” an ultimatum that makes the game different vs. the person “giving” the ultimatum? This is an asymmetric game after all.

Another type of ultimatum game in the professional setting is a job offer. The employer gives the job applicant an offer. The applicant will compare the job offer to their existing job, no job, or other offers. The applicant will determine if the offer is fair and then decide to take it or not take it, similar to the classic ultimatum game.

It’s worth noting, both sides have put in effort at this point. If the applicant accepts, both parties win. However, if the applicant turns the offer down, the employer will have to find a new applicant.

That said, in employer games vs. relationship games, there is often less emotional currency at stake on both sides. Real currency is the modicum of trade vs. love and commitment. However, in both games, there appears to be a type of asymmetry. This likely impacts incentives and power dynamics.

Sequential games: when the next step relies on the previous step

Another group of games are sequential games. This is where actions are played sequentially. Sequential games can be played with perfect or imperfection information on another player’s moves. An example of a sequential game with perfect information is chess. In chess, players know all the moves of every player before. An example of a sequential game with imperfect information in poker. Players don’t know the private hands of other players.

An interpersonal equivalent of sequential games is dating. We often hear that dating is like chess. Each individual makes a move. Then the next individual makes a move. There’s an opening, a close. Certain players have limitations in terms of the types of moves they can make. For example, the bishop can only move diagonally. Similarly, there are often limitations in terms of the types of moves certain people can make.

For example, in heterosexual relationships, men are often considered the pursuers while women are considered the pursued. Men are expected to make the first move, pay for dates, and initiate intimacy. On the other hand, women are expected to “play hard to get.” Encourage yet pull back, the modern version of a mating dance.

However dating is a lot closer to poker than chess. In poker, you don’t know the other persons’ hand i.e. imperfect information game. Similarly, in relationships, people often bluff or outright lie. We don’t know how prior relationships worked out - only the version told to you. The more you put on the table, the more you have to lose. Moreover, like poker, the stakes can be high.

It’s interesting to think of dating as chess and poker because it helps to understand that most “social rituals” are in fact types of games that people play. The steps, strategies, and processes are not mysterious but rather often rational steps made within the framework of sociocultural norms.

We see a lot of things that seem rational. People typically date within their socioeconomic class. They further date at similar attractiveness levels. They date based on personality and compatibility. That said, we live in a world of dating that appears irrational as well.

Why do some people ghost? Why do people in healthy relationships cheat? Why do individuals stay in toxic, abusive relationships? Why do arranged marriages last longer whereas marriages based on so-called love lead to higher divorces? Why do people fall in love? Why do people fall out of love?

I wonder what part of this can be explained by hidden incentives (i.e. subconscious motivations) and asymmetric information? Probably not all but likely more than we think. This is how psychologists and behavioral economists try to understand people and the world. Through a lens of rational irrationality.

Repeated games: when the battles make up the war

Repeated games are played multiple times. An example of a repeated game is a long-term relationship or marriage. In this game, an individual knows the game must be repeated over and over again. If you forget to do the dishes once, perhaps it’s fine. However, in the next *game,* your partner may get upset and bring it up.

This is a negative - suboptimal - outcome for both parties. On the other hand, if you do the dishes consistently, this may create a positive influence on future games. Your partner may reciprocate appreciation in other ways. Most relationships have this type of “give-and-take” where both parties know the game is played over a repeated period.

Another kind of interesting way to think of repeated games is in the relationship with yourself. We each play these repeated games of mastery, discipline, self love and compassion. How often do we beat up ourselves over mistakes, only to find this leads to negative outcomes in the next game. How often do we sleep late, scroll through social media only to find ourselves on the losing side of the tomorrow game.

This concept of “later me” is well studied. I had a professor in undergrad put out this intriguing study on how engaging with your older self as a real and relevant version helps people make better long-term decisions. Many successful books on self-improvement and health begin with the concept of the “end in mind.”2

Complexity of relationships and games: being human

I find it insightful to think of relationships as games. Games are “maps” or simplified models to help you chart the territory of various relationships. Games often have an optimal strategy, payoffs, and incentives. People are often more predictable than we think they are. However, games are often more complex than we expect them to be.

It’s important to remember the mental model that “maps are not the territory itself.” A game theory framework provides a simplified example of what goes on in a relationship. It will never fully give you insight into the complexity of a situation, relationship, or person.

People often have subconscious biases, insecurities, and secrets that drive their actions, often without them knowing. The most concerning bias I’ve noticed is the “I’m not biased” bias. The people that are so unaware of their deeper motivations or willing to question their actions. Incentives are as complex as humans themselves.

https://neilkakkar.com/games-people-play-blogpost.html

https://hbr.org/2013/06/you-make-better-decisions-if-you-see-your-senior-self